Children and adolescents most often experience sexualised violence in the family and the survivors’ board is focusing on this crime scene. As part of its own "Family" working group, it works with various forms of prevention and help offers as well as dealing with the situation in context. Through their networking with other experts, they aim to overcome the widespread culture of covering-up and remaining silent and they see developing an intervention ethos as a task for society as a whole. On this page you will find a compilation of the family crime scene activities undertaken by the survivors’ board.

More details about the family symposium

can be found here

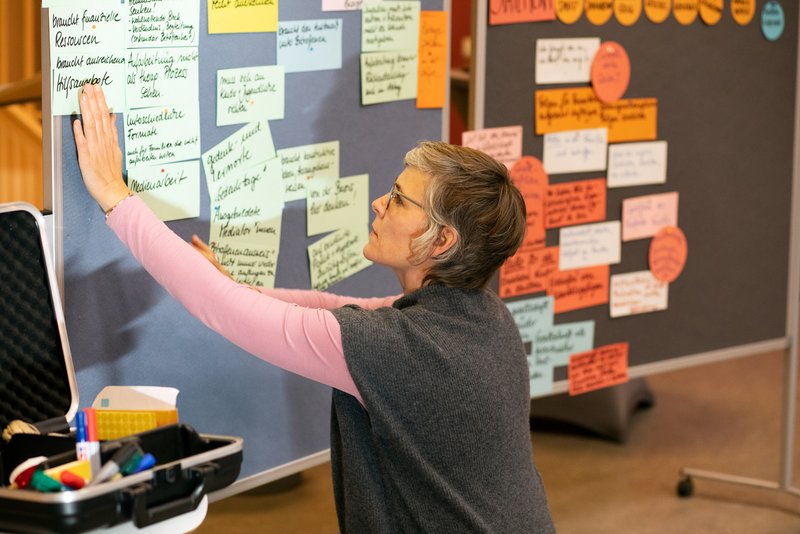

Survivors’ Board voices during the discourse workshop

“It is a task for society as a whole to overcome the widespread culture of covering-up and remaining silent when it comes to sexualised violence and to develop an intervention ethos. The family as a crime scene must finally be taken into consideration.

We need more critical reflection on power structures within families, gender roles, traditional family images and restrictive value systems that are passed down from generation to generation and promote psychological as well as physical and sexualised violence in the family.

Children and adolescents have the right to grow up free of violence. It is a task for society as a whole to protect children everywhere from experiencing sexualised violence, to recognise the signs at an early stage and to take appropriate counter- and preventative-measures”.

"Every adult is responsible for protecting children and adolescents in families. This includes addressing sexualised violence and children's rights whilst assuming that there are probably survivors of sexualised violence and perpetrators in every family.

In families, despite disclosure, it is usually the perpetrators who remain integrated, while those who suffered are left alone and bear the burden of trying to come-to-terms with it. Active covering-up by existentially important caregivers in the family then continues. For those who suffered, this is also stressful and hurtful. Quite often, the only option left for the survivors is to break away from their family of origin”.

"It's not just about abuse in the family as if it were a singular phenomenon, but also about abusive families where little was really right even before the first sexual assault happened!”.

“'Home' was no longer a safe place after the first assault by the perpetrator and never has been safe again”.

Selected images from the discourse workshop

The survivors’ board in action with other invited experts

Voices of other experts speaking during the discourse workshop

During the discourse workshop the invited guests opened the discussion rounds with their introductory statements.

You can read the statements of the experts on issues such as an intervention culture, prevention concepts in families as well as investigation and support for the survivors and their families here.

An intervention culture - prevention concepts in families as a task for society as a whole

First of all, I would like to thank the authors for the very helpful "Sexual violence in the family" study as well as the survivors board for the "Family as a crime scene" discussion paper and for organising and implementing the discourse workshop about this issue.

The case study

- confirms what we have known and said publicly for over 30 years at information events, in our public relations work, in our training courses and it also

- confirms what we have been seeing for many years in the statistics on the use of the Violetta specialist counselling centre for sexually abused girls and young women: nearly half of the girls who come to us for counselling have experienced sexualised violence in their immediate or extended family environment.

- Around half of those who suffered were abused as children and a large number were assaulted during preschool age and

- most of those who suffered only came forward to us during adolescence or when they were young adults.

So the “family as a crime scene” should actually be anchored in everyone's consciousness - but this is not the case, which the study also confirms.

What are the reasons for this?

Family is all too often regarded as being a private matter. It is obviously difficult to challenge the family image or to question it.

Even in this study it seems important to note that “the majority of new-borns are well received in whichever family constellations are formed and that the majority of children feel protected and loved” (see August 2021 issue, pages 20 and 21) - as if we always have to apologise when we list the facts about a crime scene family.

I wonder why this is still the case and I find it absurd: just imagine that in institutions such as the church it was mentioned again and again that in the ecclesiastical context sexualised violence against children has occurred and it still occurs very often, even though the church as an institution is actually doing a good overall job.

Hence my first demand: the public relations work undertaken by the specialised counselling centres is not enough – in addition professionally well-designed and financed nationwide campaigns are also needed - with the aim of raising social awareness for this crime context.

Regarding the question: What is needed to be able to create prevention concepts in families?

In my opinion there cannot be a family prevention concept that is similar to one used in institutions as other measures are needed to improve how children are protected in families:

- First of all, we need to turn away from the socially-idealised notion or wishful thinking that the family - and not just the traditional family - is a safe haven and guarantor of the protected upbringing of children as well as away from the dogma of the family always being seen as a private matter. As we all know, the causes of sexualised violence during childhood lie in violence arising from gender relations and the balance of power between adults and children, as well as their dependence on adults. They are prevalent in families.

It is also important to raise public awareness that sexualised violence occurs in all milieus - i.e. in middle-class, alternative or left-wing milieus as well - and the higher the perpetrator’s social status is in the respective milieu / society, the more severe it seems to be.

So that supporting family members can look into it and provide protection - and in most cases this means the mothers - it must also be ensured that they are financially secure when they separate - this applies

- to women who are in a precarious financial situation as well as to women who were living in middle-class or well-off marriages.

- This means that social political efforts are needed that will provide independent financial security for women/mothers both in general as well as in the event of separation.

Furthermore, mothers who separate due to abuse should not have to fear that the Youth Welfare Office or the family court will accuse them of making false accusations against their partners in order to gain an advantage for themselves.

When regulating custody as well as access rights, the facts about the abuse must be taken into consideration, so that a father who has abused his daughter or son is initially not entitled to access or custody.

There is a need for mandatory staff training in Youth Welfare Offices and courts that covers the extent, dynamics and consequences of sexualised violence.

There is also a need to correct the "survivor image", i.e. one's own idea of how those who have suffered should conduct and express themselves.

What else is needed?

Due to

- isolation within the family

- the dynamics of silence and the perpetrator's communication that sexualised violence is "normal"

- the ambivalence, the loyalty and the assumption of responsibility for the family’s cohesion or for protecting their siblings

and children outside the family also need information about sexualised violence, children's rights and support services.

This problem needs well-trained and reflective educational professionals who dare to address the issue in a way that is appropriate for children and adolescents and who will also list the facts of "sexualised violence within families" as well as pedagogical material for this work.

There must be an obligation in day-care centres and schools to implement regular prevention projects. These projects should act not only to inform and reassure children who have suffered abuse, especially when their right to integrity is not being respected, but also to tell them about their right to counselling and about support services (which, of course, must also be well-equipped and easily accessible to all groups of survivors).

The new Section 8, Paragraph 3 in SGB VIII - "Children and adolescents have the right to counselling without the knowledge of the legal guardian, provided that the purpose of the counselling would be thwarted if the legal guardian was informed", must be implemented.

Prevention must not have an alibi function that leaves the responsibility for speaking out with the children. The actions of those responsible must be based on the rights of children. They have the right to have protective measures geared to their needs and that their parents will not be involved necessarily immediately after disclosure, and to know that protection and the initiating of appropriate measures will have priority.

It must be enshrined in law that the right of girls and boys to integrity will always take precedence over parental rights - i.e. children's rights are enshrined in Basic Law and must be adhered to in all measures taken.

What does it take to anchor the investigation with the family as a crime scene context in society as a whole? - What sort of support do the survivors need so that families can face up to this?

The most important thing for me is: recognising that the sexualised violence issue was only brought to public attention since it was exposed at the Odenwald School or Canisius Kolleg, but that the survivors have also been speaking out since the 1980s.

And they were often survivors from the family abuse context.

"Fathers as perpetrators" was the name of a book published in the early 1980s

There were the first self-help groups and congresses.

Let’s move on in this discussion!

There is much speculation as to why this is so.

- Both were elite schools.

- Men as survivors have spoken out.

- Institutional abuse is easier to look at than internal family abuse, as there is a possibility to distance oneself from it.

A major public campaign is needed to draw attention to sexualised violence within the family- to the dependencies, the ambivalences, the loyalties of family members who have not been abused, to the knowing and unknowing members of the family as well as to the dynamics and the consequences.

Survivors of sexualised violence - especially if it happened in the family environment - have an enormous feeling of guilt and shame, which prevents them from speaking out. This must be addressed publicly in order to provide relief and promote recognition.

Furthermore, it is important to me, following on from the fact that the survivors have now been speaking out for over forty years, to broaden the view of those who suffered and to recognise that we are the ones who have established counselling centres, that we are politically committed, that we use creative forms of public relations work such as art projects and are therefore incredibly strong.

What is needed beyond?

- Analysing the transgenerational transmission of violence and concepts - ultimately this is also important for protecting children.

- The legal possibility of separation from the parents and being released from all parental financial obligations

- Independent financial security, such as the possibility to apply for financial educational support or training grants independently of the parents, as well as basic income support or other transfer benefits.

There is also a need for a separate committee for exchanging and developing these demands as well as including survivors and their expert knowledge - this discourse workshop about the "family as a crime scene" is a good start.

An intervention culture - prevention concepts in families as a task for society as a whole

When preparing for today I looked again at the very basic prevention concept modules / principles and tried to apply them to the family context. Developing a prevention concept must be based on the following principles:

- Risk analysis

- "Culture" in an institution, rules for dealing with each other

- Procedures when intervention is necessary

The first principle - risk analysis:

Ultimately, fundamental information and analyses about the risk to children and adolescents have been available from the women's movement environment since the 1980s at the latest. It was primarily women who had suffered sexualised violence who drove the knowledge generating process. In this sense, participation, which is also a very important point developing prevention concepts, was more than a given from the start. However, this important principle must always be actively remembered.

The study completed by the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse also provides another important module. So we have a good basis here, even if certain aspects should definitely deserve further scientific research.

The second principle - social interaction culture

When applied to the family as a crime scene context, a change in "culture" and social interaction means developing a different social image of what the family is and clearly strengthening the rights of children and adolescents:

- a child needs more than two caregivers for a healthy development. In fact the image of father, mother and child has long been outdated, but is still legally constructed in this way. There are families where three, four or even five people of different genders take responsibility for a child. It must be possible for several people to be entered in the birth certificate as responsible persons with the corresponding rights and obligations, two mothers, two fathers and, for my sake, stipulated “godparents” as well.

- Children's rights must come before parents' rights! Children's rights must be included in Basic Law. Convicted perpetrators must never be given custody again and there must be no unaccompanied right of access. There needs to be a “right to divorce” for these children from their abusive parents.

- Participatory developing of complaints and help options for children and adolescents.

- There is a need for parent training that embraces all parents. It is important to keep in mind that parent training courses cannot prevent sexualised violence, because the perpetrators do not lack knowledge about the harmfulness of their actions. Parent training is important for potentially supportive parents.

- Training for the wider environment such as medical, educational and legal staff and everyone else as well.

The third principle - procedures:

- Changes to the legal framework are needed (e.g. lower thresholds that will enable the Youth Welfare Office to intervene early on)

- Intervention options in the environment must also be improved and low-threshold, anonymous counselling options are also needed for the supportive environment. They must be established throughout Germany, especially in the countryside.

- Children and adolescents must have access to support services and accommodation options without their parents being involved.

- Clear positioning of the immediate and wider environment in relation to the perpetrator is absolutely necessary! What is actually needed here is social ostracism of the perpetrator. The costs of the offence must be higher for the perpetrator than the benefit.

- In this context, I would like to see an independent evaluation of previous approaches to working with offenders.

Investigation / Adult survivors

Successful social justice can only take place with the structured and assured involvement of the survivors. As previously mentioned in the study, participatory approaches are needed at all levels and in all areas of the issues. In fact even survivor-controlled projects into research, into prevention and at the support services level are imperative in order to really advance social justice.

In the context of social justice, the focus often shifts very quickly towards prevention and those who suffered are lost from view, so I would like to take a closer look at a few aspects, especially those of young adults.

The situation of people who are or have been subjected to sexualised violence in the family context usually remains precarious in many directions far beyond the age of 18. On the one hand, violence often does not end when a person reaches the age of majority, especially if financial and other dependencies still exist. The perpetrator's parents sometimes have legal custody in the case of people with mental disabilities, i.e. there is no escape from sexualised violence for these people. These dependencies are perpetuated by various legal foundations (e.g. Hartz IV benefits, parent-dependent financial educational support or the current legal care system). On the other hand, even after the violence has ended and they have possibly moved out of the parental home, the situation for the survivors will remain difficult for a long time, not only emotionally and financially but also in everyday life matters.

In this context, new legal foundations urgently need to be created and adapted to meet the situation of young people who have suffered sexualised violence in their family environment.

It must be possible for these survivors to legally detach themselves completely from their parents and there must also be no more dependencies.

Furthermore, in order to make it possible for individuals to come-to-terms with their suffering, there is a need for:

- family-independent access to financial support during training/school/studies (financial educational support that is independent of parents or better still, an unconditional basic income).

- Emotional support and guidance during training, because it is doubly and triply difficult without family support. I am not thinking of employed social workers here but of other survivors who are more experienced in life. This support could take the form of mutual exchanges. But specific coaching and even accompaniment (e.g. when going to the authorities) would also be possible and it would certainly make sense. Of course, all this would have to be adequately paid for, and in these contexts, a living prevention concept would also be needed.

- Affordable housing, so that people can live alone if necessary, but also in shared flats and with or without care, depending on their needs.

- The legal care system needs revising as it should be taking into consideration the fact that parents can also commit sexualised violence.

Intervention culture

I think the discussion about a new family model is important, especially discussions about the family as a private world vis a vis protecting children from sexual violence.

I would like it to become the standard that parents must continue their training. Today there are various ways of living family life and raising children. Nothing is predetermined. Parents can and must make many decisions on their own. Some examples: How should the children be brought up? What are our values and aims? How do we control them?

Parent courses or a parenting certificate can provide support and have a preventive effect with regard to the protection against violence issue. This qualification must have a low threshold be easily available to all parents free-of-charge. There are many good concepts, e.g. the DKSB parenting course, which is available for different target groups. (Attention! There are also questionable concepts that have nothing to do with protecting against violence or children's rights - of course, I don’t mean these courses).

This also includes a change of meaning: anyone who seeks support, networks the family externally and provides insights into imperfect conditions is competent and not overwhelmed.

I advocate that children should also have a reliable caregiver from outside the family. From birth there should be someone who feels responsible for the child and builds up a good relationship with the child. This could be specialists, neighbours, surrogate grannies or volunteers. These surrogates are entitled to training with regard to healthy growing up and preventing violence.

Facilities where children spend time also need to be better equipped. Children are spending more time in institutions today than they did 20 years ago. This is an opportunity that should be seized. We need sufficient competent staff for providing good care and for constructive work with parents.

On the other hand, each individual bears responsibility.

It is important to raise awareness of when violence and the abuse of power begin.

And: How do I to intervene if I suspect that something is wrong.

This needs guidance. What can I specifically do if I suspect violence in my neighbourhood, amongst my acquaintances, or if I see children being treated badly in public?

Awareness that violence can happen anywhere and often has to be created.

Justice for adult survivors:

What will it take to anchor social justice with the family as a crime scene context in society as a whole?

I will list some specific ideas in the following. The list is incomplete due to the time limit of 3 minutes and some points need to be elaborated on.

Well-known, but nevertheless central: adequate support is needed to move on from dealing with the consequences to coming-to-terms with them.

An institution at the federal or state level must be permanently responsible and commissioned to ensure and shape the process of coming-to-terms with the past.

This could be an Independent Inquiry Commission in the family as a crime scene context. Analogous to institutions, the state is the institutional opposite in the family as a crime scene context. It shares responsibility for the structures that make abuse in families possible in such a large scale.

Many survivors have told their stories to the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse during the hearings, many have dealt with them in therapy or have otherwise made it clear that they were survivors of sexual abuse without having to go through criminal or OEG proceedings, which at best will result in social recognition through a judgement. In order to get access to compensation or aid, survivors always have to explain in detail about what was done to them. This is an additional burden. One idea is to create an ID card that the survivors can get after a hearing, which proves that they have suffered. This card could provide access to compensation and support, etc., without them having to tell their stories every time. It would be similar to the severely disabled pass.

Survivors in families must be able to tell their story. Other decentralised but official services are also needed, in addition to the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse's offers, for those who do not contact the Independent Inquiry, so that the stories can be heard by representatives from society. Further research using the reports is needed and they could be an opportunity to raise awareness in society of the extent and consequences of sexualised violence suffered during childhood. The form in which this would be possible must be studied.

We need a place for the stories, e.g. a research and reminder centre.

One of the conditions that would help survivors to come-to-terms with the past is the possibility of networking and advanced training. The state must make resources available for this and provide easy access for the survivors.

Coming-to-terms with the past can take place on a societal level as well as in individual families. It would be helpful to have guidelines for survivors and families to help them come-to-terms with the past. Analogous to the guidelines for institutions.

It would also make sense to have an entitlement to free external monitoring / support / moderation / mediation.

A report should be submitted here at the end of the processes in which the results, agreements or even failures are recorded. This can be a document for those involved and it should also be available for research purposes.

There is a need for Child Sexual Abuse Commissioners in the federal states that are responsible for helping the survivors and for promoting local and regional survivors’ networks.

I continue to advocate for a central compensation fund for all survivors, regardless of the context involved. There must be a common understanding regarding compensation claims, independent of the crime context and the willingness of the relevant perpetrator (or group of perpetrators) to pay compensation.

There are still many unanswered questions about investigation with the family as a crime scene issue. Therefore research projects and discourse workshops must continue to be funded.

An intervention culture – prevention concepts in families as a task for society as a whole

The range of #TatortFamilie issues is complex and extensive. I welcome the fact that with this discourse workshop, the public focus is once again being placed on the topic of abuse/sexualised violence in the family and in the family environment, which is still very much a taboo issue. Since the 1980s at the latest, many survivors and committed, mainly feminist, counselling centres have repeatedly drawn public attention to the immense extent and consequences of this violence. However, they are only sporadically listened to or most of the time and in keeping with the "patriarchal tradition", discredited as being hysterical or even accused of perpetrator/survivor reversal.

Sexualised violence in the family is an issue that involved us precisely where children are supposedly safest and where we were always supposed to be protected. It is an issue that those of us who suffered inevitably had to face. We did not choose it and for a long time no one listened to us apart from the counselling and therapeutic specialists. The fact that people are finally listening, looking, researching and - what is much more important and must result from all of those who listened if we are really serious about protecting children - looking for solutions and asking for social changes, has at least changed during the last ten years and since the disclosing of the abuse cases at the Odenwald School and in the Catholic Church and more recently through the family cases in Staufen, Münster and Bergisch Gladbach that were made known. But sexualised violence against children and adolescents is still considered to be outside of us as a family and society, as something that takes place "out there" with celibate clergy, in clubs, in schools or by anti-social and "monstrous" strangers. Even if, or precisely because it hurts, we must finally fully acknowledge that this is not true and that excluding violence and its consequences from our private and social environments is deceptive. Because both perpetrators and us survivors, regardless of the context of the crime, are part of this society. We are all socialised in, with and by society.

Sexualised violence against children and adolescents strikes right at the heart of our society. Just as it was and still is mostly impossible for us survivors not to face up to the consequences and effects, it should not be possible for us, as a society, to evade them. It is not enough for us survivors to have to undergo therapy before we can "function" again. And it is not just us survivors who have to come-to-terms with the abuse and bring about effective structural changes in society in order to protect children today and in the future.

I have focused on a few aspects that address this fundamental social dimension for this family as a crime scene discourse workshop:

- An intervention culture requires a fundamental paradigm shift in society, a change in its perspective. Society must move away from "I don't want to accuse anyone unjustly, it's none of my business, it's their private affair" and towards "it's better to get more "non-committal" information (e.g. from UBSKM’s nationwide Sexual Abuse Telephone Helpline, which is free of charge and anonymous) than to leave a child to its fate and expose it to continued sexualised violence". The idea of family as a private world must be reviewed, widely discussed and re-evaluated. What does it mean for children - whose privacy and intimacy is being horribly violated in the very place where they should be protected and supported - to be left alone with and in their families? Just how worthy of protection is the “privacy” family value when it is used as a shield of “silence” about continuous acts of abuse? It must be made clear that if I, being a neighbour, a teacher or a doctor, don't make the minimal effort of making a phone call, then at the worst I risk exposing the child once again to the perpetrators. Violence is never a private matter as no child can protect itself alone.

- There is still a need for a fundamental and broad social knowledge about the immense extent of sexualised violence against children and adolescents in the family as a crime scene context and an awareness of the consequences for society as a whole. Sexualised violence is not an isolated incident, it occurs in all social classes and is usually not inflicted by strangers. It does not occur in a vacuum, it has its roots in social, family, cultural and political relationships. And it also has consequences not only for those who have directly suffered the violence. It also has a direct impact, after disclosure at the latest, on the lives of parents, siblings and other people close to the family. It shapes and affects all family and social relationships. If it is not handled and/or worked through together, it will continue to have an effect and it is also possible that it will be passed on to the following generations. If we can break the "circle of violence", then the entire family dynamic will change and we will be able to protect children in the future and perhaps, relatives who have not yet dared to look at their own traumatic experiences will have the chance to do so. Awareness and the recognition that sexualised violence against children and adolescents is not only a specific fate for those who have suffered, but that the assaults also have far-reaching consequences for society as a whole, can also make a decisive contribution to removing the taboos surrounding this violence. Above all, it opens up the possibility to look at which social structures aid this form of violence as well as all other forms of violence against children and have actually helped it for decades. (For those who can be convinced by economic arguments - the costs of therapy for relatives, etc., should also be included in calculations for trauma follow-up costs, https://beauftragter-missbrauch.de/fileadmin/Content/pdf/Literaturliste/Publikat_Deutsche_Traumafolgekostenstudie_final.pdf)

- Systematically structured knowledge about the extent of sexualised violence, perpetrator strategies, recognising possible symptoms, trauma consequences and intervention options (Sexual Abuse Telephone Helpline as the lowest common denominator), etc., should be anchored in all professional groups and in all areas (e.g. sports, youth groups, clubs) that work with children and adolescents. This should be either in the form of compulsory further training and/or by including this knowledge in the training curricula.

Young parents should also receive information from the beginning about how they can protect their children from sexualised violence. This could be in the form of a brochure that does not scare people but addresses the issues in a low-threshold and everyday way, such as what are the possible signs of sexualised violence, that boundaries should be respected even in children, where do these boundaries begin, what constitutes behaviour that violates these boundaries and what should/can still be allowed and where they can seek advice if they suspect it, etc.

- See where discussion rooms can be started or provided. In schools, kindergartens, as VHS lecture series?

- Books/brochures about "right and wrong behaviour" in families, not only in relation to sexuality but starting with respecting boundaries and meeting needs.

There will be no attention paid without publicity:

- Publicity campaigns (in the tenor "I am/We are not (a) dark figure(s)", "Abuse also affects you" or similar).

Investigation / Adult survivors

- In order to lower the threshold for families to come-to-terms with abuse, it is necessary - provided that they have not been directly involved in the abuse or have made it possible by looking the other way and remaining silent! - to also have a "sympathetic view" of the relatives of those who have suffered and/or information about the effects on the entire family system and especially about perpetrator strategies. Relatives in families in which perpetrators have managed to commit their assaults systematically and deliberately and to keep these assaults secret have also been systematically clouded in their trust, been deceived and betrayed. Many have to struggle with feelings of guilt for not having protected the survivor and for not noticing and stopping the abuse. They also need support and should be seen and listened to in their secondary anguish so that mutual coming-to-terms can succeed.

- Investigations within the family is not something that can be done alone, because of the emotional turmoil caused by the offences. It would be conceivable that family members and those who suffered directly could be accompanied by trained professionals, e.g. mediators for an out-of-court conflict resolution. This could also make it possible to work through the problem with the perpetrators, based on the "survivor/offender mediation” model (https://taeter-opfer-ausgleich.de/). However, the conditions for this are that the perpetrators repent their assaults, take full responsibility for them and that the survivors also want this.

- There are families who do not want to or cannot come-to-terms with it. But even in these cases, the survivors have a justified claim to social recognition and justice. What alternative forms/formats can there be so that the suffering that the survivors have endured is acknowledged and their previous coping and life achievements are honoured? Alternative justice forums/meetings with symbolic tribunals, such as those that have already taken place in the case of sexualised war violence?

- Public relations policy work can also play an important role in coming-to-terms with the past. This could be in the form of an official reminder place for learning about the "sexualised violence against children and adolescence” issue. Survivors’ stories could also find space here in addition to providing facts about sexualised violence against children and adolescents. These stories could illustrate the extent of sexualised violence, enable other survivors to connect with their own stories and show how diverse the suffering was as are the ways of coping with it. However, these stories should not be left on display for the purpose of "shock entertainment”. Survivors have already told their stories far too often without any “lessons being learned”.

Existing commemoration days such as the European day against sexual violence against children and adolescents that is held on the 18th of November, could also be used for broader public campaigns and networking. Statements by public figures such as politicians, are not only an important signal to the survivors that their suffering is recognised and that the assaults are condemned, but they also contribute to bringing the culture of "silence about violence" into focus and removing the taboos from society.

-

Up to now, the survivors have often been left on their own to come-to-terms with what they have suffered. Information, help and support all have to be collated separately and from different systems. This usually takes a lot of time and energy and reinforces/confirms the feeling of being alone, which is often present among the survivors and the fact is that they are often left alone. It could be helpful to set up nationwide "everything under one roof" contact points for adult survivors similar to the “childhood houses” initiative that has now been established (https://www.childhood-haus.de/), where they can find central information/counselling/support for coming-to-terms with their situation as well as finding trauma therapists and get legal advice about deciding whether or not to report their perpetrators, etc. The mediations mentioned above could also take place here and survivors’ networks could also be organised.

These contact points must also be promoted at a federal policy level and, above all, they must be financially secure. The mostly precarious working conditions of the specialised counselling centres have shown that protection against sexualised violence inflicted against children and adolescents as well as supporting today's adult survivors has not been understood or addressed as an issue by society as a whole.

An intervention culture – prevention concepts in families as a task for society as a whole

The wall that needs to be breached here is the relationship between family and society. The heterosexual nuclear family with father, mother and child is considered to be the nucleus of society. Only when the parents fail or the child is neglected will society intervene.

Society does not declare any self-interest, but only becomes involved for child protection reasons.

Yet it is so simple: sexualised violence damages social coexistence and every society should make a stand against it for self-preservation reasons. I believe that only through self-confidently formulating the interests of society can we counteract the sanctity of the family.

But what can be tackled today, even before we have broken through the wall and without therefore drilling less?

Specifically I can initially see three points here:

-

- Analogous to the point of the recruitment criteria in the prevention concept for institutions, it is also about the point of who actually becomes a parent. Now, we cannot control this in the same way as a driver's licence is needed to drive a car, but we can

- qualify parents better, offer more parenting courses, etc.

- A refusal to qualify must be answered with increased controls (for this we will need reinforcing by the Youth Welfare Office).

- Convicted perpetrators should no longer be granted access rights and absolutely no custody rights in the specific cases and this must generally apply in the future as well.

- When it comes to behavioural agreements in institutions, there is the principle of intervening not only in cases of severe sexualised violence, but in boundary violations as well.

- This means nothing less than lowering the intervention threshold for the Youth Welfare Office: the risk to a child's well-being starts much earlier than severe sexualised violence.

- And it needs a clear call to the environment: get involved: it is not defamation if you call the child emergency services: even though you might be called names, it is important that you intervene if you see a child is being belittled.

- For clarification, we finally need children's rights included in basic law.

- Furthermore, we also need broadly communicated guidelines about how parents should treat their children.

- Behavioural agreements are of no use without complaint authorities and procedural channels.

-

The Youth Welfare Office currently functions as an independent complaints authority. If this is to continue, then something has to change: the work must become more low-threshold and better known. This is about child emergency services having the skills and the possibility to intervene. These facilities must be adequately outfitted. (Telephone helplines for just chatting with volunteers who can't do anything in real life are not a complaints authority, but a suggestion box that is never emptied or read).

-

The procedures must be continually reviewed and improved. In other words, the work of the Youth Welfare Office must be reviewed.

-

- Analogous to the point of the recruitment criteria in the prevention concept for institutions, it is also about the point of who actually becomes a parent. Now, we cannot control this in the same way as a driver's licence is needed to drive a car, but we can

I think the direction has become clear:

- Develop the self-interest of society and simultaneously develop

- advance prevention concepts through

- supporting the parents + improving parental control

- Strengthen the position of children

- Earlier intervention by the environment and the authorities

- Support the child emergency services through giving them more powers.

Investigation / Adult survivors

Coming-to-terms with the past always has two dimensions: coming-to-terms with the individual case and coming-to-terms with the failure of the "institution".

Coming-to-terms with society

This is where the debate is just beginning: A direction has been set in the study carried out by the Frankfurters. This needs to be substantiated. But please, not just in studies but in social discussions: events are just as much a part of this as books, films, etc., and even studies. Especially those that are more than just "telling stories". Please do not misunderstand me here: telling stories is important, I don't want to devalue that, but coming-to-terms with it means looking at the causes and not just specific ones, but structural ones, spiritual or ideological ones, economic ones, etc. Talking about sexualised violence in families without talking about patriarchy is the same as talking about a disease but limiting yourself to certain external symptoms. So there is still a lot to do here and we urgently need strategic planning. This also includes the need for strong survivor presence. In other words organisation.

Case-related investigation 1: survivors

It is easier to look at the aspect of coming-to-terms with the past separately. I don't want to go into the personal work involved in self-help or therapy here - I would rather call that treating. As I said, coming-to-terms means breaking down the background and not dealing with the consequences. Even though they interact, they are still two different things. In my opinion, this point has been neglected so far, especially in therapeutic work. Being survivors means that we have had to develop our own methods in order to be able to come-to-terms, which is understanding the causes and reasons behind the assault. It doesn't help to adopt myths from the perpetrators offences without reflecting on them and we can't pass this on to a specialised counselling centre in accordance with the slogan that ‘they should do what the therapists don't do’. We ourselves have to find ways of doing something like this, of course with all the support that we need. Self-help approaches already exist.

Case-related investigation 2: Family

There is also an aspect of coming-to- terms with the past that has not been considered so far: coming-to-terms within families. How do those members of a family who were not directly involved in the assaults come-to-terms with sexualised violence? How did it come to sexualised violence and were you involved at all? Where were the blind spots and how did you fail to see what was going on? Do you have any responsibility for failing as a family?

And all this was without the survivors being able to do anything, as is normal. It would be best if the coming-to-terms with the past process was organised in such a way that the survivors could freely decide for themselves whether and how they want to participate.

Families will need support for this, as do institutions: it needs special family coming-to-terms counselling. So far, this approach remains absolutely underdeveloped as we mainly receive requests from specific individuals in families, never from the entire family. I strongly suspect that the educational and family counselling centres do receive such requests either. Methods and requirements urgently need to be developed and staff will need to be trained accordingly. It is all about establishing a new professional sector, family coming-to-terms counselling and interfacing between the educational and family counselling centres and the specialised counselling centres.

What I said about the survivors coming-to-terms with the past also applies here: dealing with your own trauma and disappointments must be kept apart from coming-to-terms with and taking responsibility for your own failure.

I would also like to add one more thing: it must be possible to cut the economic ties between children and their parents after sexualised violence. Whether it is Hartz IV, financial educational support or care, we need a law that can divorce children from parents who inflict sexualised violence. This law is simply overdue and we have already developed specific proposals for implementing it.

So to summarise:

- Coming-to-terms with the past at a social level that will deal with the family structure and how it fosters sexualised violence,

- in addition to dealing with the consequences of sexualised violence, which focuses on the specific question of how and why and

- coming-to-terms by the non-perpetrators of the assaults, which should aim at understanding why the sexualised violence occurred and what your own part in it might have been.

These are the three building blocks of coming to terms with sexualised violence in families.

In my "POSTCARD TO DADDY” documentary film, I made the coming-to-terms process with sexual abuse by my father transparent with my family and encouraged other survivors to speak out about the unspeakable, which goes far beyond my own healing processes.

But what can be done when relatives suppress it, deny it or are even suffering themselves? What can be done to prevent sexualised violence in the family context? Recognising the signs and nipping this violence in the bud as well as a culture of listening then intervening and asserting children's rights are needed here. This also includes the courage and the parental responsibility for pedagogical training, a specialised counselling network with an adequate budget, support for the survivors so that they can be heard by society on a representative basis as well as an investigative scientific body tasked with making its findings about sexualised violence against children in families accessible to as many people as possible.

To the extent that our own behaviour in terms of climate protection is no longer a private matter, child protection, the right to live in a home free of violence, educational equality, physical and mental health and love should be the future of our children.

A family is the smallest emotional institution with its own cosmos.

As they are especially protected by law, families are widely seen as being a safe place for children. In a best case scenario, children will be guided in their families to learn to do things by themselves, be allowed to let their own thoughts evolve and develop their individual personalities.

But families that pose a danger to children also exist. Seemingly concealed, this type of family becomes a crime scene for children. A crime scene in which sexualised assaults rob children of their privacy, damages their intimate vulnerability and hinders how their identity and personality develops. Even today signals that children send out are often misinterpreted, overlooked or not taken seriously enough. Even when children change their behaviour or their behaviour becomes inappropriate for their age. In many cases, it is still taking far too long for the environment, even the specialist one, to react. Despite prevention and today's better opportunities for getting specialised, anonymous and low-threshold counselling.

Although it is known that children of all ages who are suffering from violence are usually unable to free themselves from the assaults in the family.

The need to intervene must be specifically communicated to adults through education. Adults in every environment should see themselves as having a duty to provide targeted support for children who are not doing well in their family. Child protection must also understand that cultural, religious and structural practices exist in families as well as individual attitudes. Structural conditions can promote or hinder children's rights. Trends and attitudes in society are not excluded when it comes to establishing prevention concepts for and in families.

The fact that we are currently talking about prevention concepts in families has been long overdue. This family case study makes it clear that sexualised crimes in families are not a private matter, but that they concern us all. For this reason alone, politics and society must finally commit themselves more consistently to making the required resources available.

This includes anchoring training guidelines everywhere on a national level. This will ensure that children's rights and child protection are widely distributed as a knowledge culture and this will have an impact on the population. There will be a simultaneous need for sufficient and well-prepared specialists in various fields. An important point here will be to create solidarity structures that are also willingly supported and accepted by healthy families.

It is time to establish prevention concepts in families so that they are understood and needed as a natural part of protecting children. They will then become a medium that enables adults to recognise dangers to children and then intervene. Then no child will be left alone in the future.

Investigation with the family as a crime scene context is essential.

Especially as today's adults know what it was like, the structural conditions that exist in families as well as in society that have resulted in many not receiving help. Investigation with the family as a crime scene context is inextricably linked to successful child protection today and in the future.

At the same time, I have experienced the consequences during my own life through my commitment the far-reaching, often long-lasting secondary consequences of sexualised crimes find their way into the lives of those who survived. In their reports, the survivors describe what might be or is still bothering them both as part of their anonymous self-help and away from it.

They talk about how little others have done to protect themselves in this crime context. Despite knowing what was going on in the family. There are also cases where a large environment knew what was being done to the child. Others have also tried to free themselves, left the family early or even reported the perpetrators. In several cases known to me the lack of protection from manipulative relatives or the environment led to no criminal proceedings taking place.

Coming-to-terms with the past is clearly linked to social and political responsibility. The stories told by many people make it clear once again that social attitudes and current trends, a lack of child protection and structural taboos are all responsible for the fact that no help was available for many survivors. The suffering that was inflicted was tolerated over a long period of time. This is precisely why politics and society have a duty to recognise and alleviate injustice. The structures needed for this must be needs-based, aware of the survivors, ensure participation and be devised for coming-to-terms.

Many survivors also have a strong wish to come-to-terms with their family of origin. This will require the involvement of specialised services that have activating and supporting effects. Structures that help and communicate what has happened so that, in a best case scenario, existing dysfunctional family structures can be recognised, understood and changed by relatives. Perpetrators are usually deeply integrated in many family systems. Whereas the survivors often do not get any support from their families in their need to speak out and highlight the problem.

Coming-to-terms in families holistically highlights interrelationships that have repeatedly been put aside. Afterwards, many survivors find that some parts of their family lives have become limited, despite them having a high level of competence. Many talk about how difficult it is for them to form close, intimate relationships with others. Some deliberately remain childless in fear of passing something on. Others sometimes find parenthood a strange experience, even when they want to be good parents to their children. Society's ability must be measured by how it deals with its past failings, how it is coping now and how it will cope in the future.

Written documentation from the discourse workshop

This documentation summarises essential thoughts and discussion strands, ideas, proposals and demands. Based on this, the survivor advocates from the survivors’ board will continue their discussion and commitment to the family as a crime scene context.

“The family as a crime scene context must finally be taken into consideration. It is a task for society as a whole to overcome the widespread culture of covering-up and remaining silent and to develop an ethos of intervention.

We know what it was like when no one sees the misery children and adolescents suffer in their own families. Active covering-up, turning a blind eye or just ignoring the situation becomes the normal way of life in families and the survivors are often confronted with situations where they are powerless and even traumatised throughout their lives. The right to protection from violence is a human right - no child can protect itself alone.

Society's attention must correspond to the extent to which children's welfare is endangered by sexualised violence in the family. We will engage in this discussion. We will not remain silent. We will speak out even if society wants to spread the cloak of silence again”.

Families and sexual violence during holidays

December 2020 to January 2021

For many families, Christmas is the most wonderful holiday of the year. However, it is just the opposite for many children and adolescents. Their family is neither a safe nor a wholesome place for them. The survivor advocates from the survivors’ board draw attention to family abuse at Christmas and refer to offers of help for the survivors.

"It then becomes quiet and you finally have time for each other.... Take the time to listen to the children around you, what moves them, what’s on their minds - and take it upon yourself to be open to whatever is there. Even though this might be difficult, you are not alone. Get help and support with any questions that you have”.

"Always non-stop in survival mode, with no chance of relaxing. Children suffer the most during the holidays. Who will rescue them in January when they return to daycare and school psychologically exhausted?”

“'Invisible’ acts? Relatives and outsiders often have a suspicion, but don't want to overreact and accuse parents of endangering their child's welfare. Get expert help and support!”

"As both a child and adolescent, I survived Christmas more than I enjoyed it - I wouldn't wish that on any child. Christmas is still a celebration of violation for me. Really see and listen to your children!”

“Friends: Think of yourselves! Phone or write to each other! Family: Listen and BELIEVE! Survivors: You are never to blame! Society: Sexual violence can happen at any time and anywhere. Be protectors and take responsibility”.

"Think about which neighbours you want to ring even before the holidays: When your dad freaks out again. When your uncle touches you. When your mum screams in fear. When your brother's pals drop in ... Just go!”

"Silent night, holy night is often a horrible night for children. It mustn’t be; intervene! No Room For Abuse”.

“The children’s world is often anything but perfect at Christmas. Violence - in whatever form - does not take a break during the holidays. Be attentive, offer help, get some by calling: 0800 225 55 30”.

As part of a press release, the survivors’ board at the Independent Commissioner for Child Sexual Abuse Issues (UBSKM) would like to remind you about the children and adolescents for whom the Christmas holidays mean isolation, loneliness, powerlessness, fear and violence, especially during these pandemic times. The survivors´ board appeals to society to look out and intervene when children are in need of help. The press release is available for download below.